Mclean/Shutterstock.com

With rates of antimicrobial resistance continuing to rise, the need to conserve antibiotics is becoming increasingly urgent.

In the case of acne, a limited number of alternative treatments means that antibiotics are frequently prescribed first-line, often for prolonged periods and, unsurprisingly, experts are becoming concerned about the effect this could be having on antimicrobial stewardship efforts.

Heather Whitehouse, a consultant dermatologist and spokesperson for the British Association of Dermatologists, says studies have shown antibiotic usage to be “excessive” and frequently adopted as monotherapy in acne, despite guidelines advising otherwise.

“Internationally, antimicrobial resistance in Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes; previously known as Propionibacterium acnes) — the bacteria implicated in acne — to erythromycin and clindamycin is most common, whilst tetracyclines remain relatively susceptible,” Whitehouse explains.

“Rates vary between countries … but they are rising.”

A large UK cohort study published in 2017 found that, overall, 24.9%, 23.6% and 2.8% of acne consultations resulted in prescribing of an oral antibiotic, a topical antibiotic alone, or an oral plus topical antibiotic, respectively[1]. Just 5.5% were given an oral antibiotic in combination with a topical non-antibiotic.

Prescribing rates for lymecycline and topical combined clindamycin and benzoyl peroxide were also found to have increased “substantially” in the years between 2004 and 2013.

Miriam Santer, a GP and primary care researcher at the University of Southampton, is one of several doctors and researchers who have concerns that long-term use of antibiotics for acne — both topical and oral — is fuelling antimicrobial resistance.

“If someone goes on antibiotics for their acne, they tend to be on it for at least three months”

Miriam Santer

“If someone goes on antibiotics for their acne, they tend to be on it for at least three months,” she says. “So, in terms of the overall burden of antimicrobial resistance, it has a big impact.”

Santer developed an interest in acne after witnessing her nephew’s battle with it.

After failing to use the benzoyl peroxide cream Santer had given him, her nephew approached his GP about his acne and was prescribed adapalene — a second non-antibiotic topical therapy.

Knowing that topicals can be tricky, Santer advised her nephew on how best to use it, and this time he committed to the treatment. Not only did the adapalene work to clear up his acne without the need for antibiotics, he became “positively evangelical” about its effect.

“I thought, if only there were more teenagers going around telling each other what to use, it would really help,” she explains.

Santer believes that fewer people would be taking antibiotics if they had initially received better, and more timely, advice about how best to treat their acne.

“A lot of patients don’t realise that there’s a difference between what you buy on the supermarket shelf and what you can get if you actually ask for a pharmacist,” she says.

Acne myths

“There is just so much misinformation [surrounding] acne,” Anjali Mahto, a consultant dermatologist working in private practice, says.

She cites several ‘acne myths’, such as it being the result of poor hygiene, or eating the wrong foods, or that it is something you will eventually grow out of. In fact, although acne does affect a higher proportion of younger people, with an estimated prevalence of between 80% to almost 100% in adolescents, it affects older age groups too[2].

“It’s about 60% of people in their 20s [and] 40% of people in their 30s,” explains Ketaki Bhate, a dermatologist and acne researcher at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

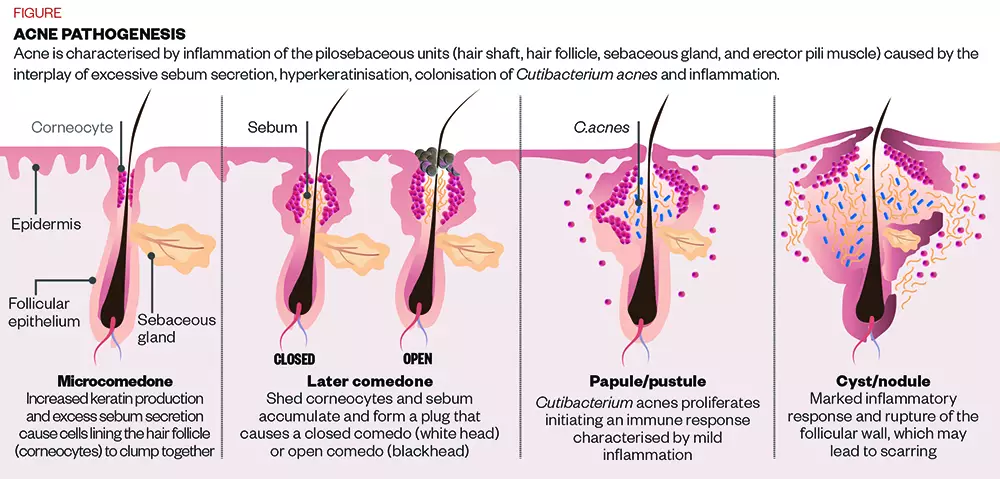

The causes of acne vulgaris are multifactorial, but essentially it is the result of an interplay between hormones and genetics, Mahto explains.

She adds that what tends to happen in people who are acne-prone is an excess of androgen hormones, which increase in puberty.

Those hormones act on receptors on the sebaceous glands of the skin, increasing their size. This results in a higher level of sebum production, and also causes the cells that line the hair follicle to get sticky and clump together; a process called hyperkeratinisation [see Figure].

“Sticky dead skin cells combined with excess oil production can block the surface of the skin,” explains Mahto.

On top of this, although bacteria naturally live on the surface of everyone’s skin, in people who are acne-prone, these include specific strains of the C. acnes bacteria.

“This C. acnes bacteria can then act on the skin and the blocked pores to create deeper red spots,” Mahto adds.

Given the role of bacteria, it is no wonder that antibiotics have been regularly prescribed as a treatment for acne for several decades[3].

However, “it’s thought by some researchers and clinicians that antibiotics work not because acne is an infection per se,” Bhate explains, but rather through a more general anti-inflammatory effect. “There’s a divide on the importance of C. acnes [in acne],” she says, continuing, “acne is not usually seen as a typical infectious disease.”

“In a lot of cases, topical [non-antibiotic] treatments are just as good [as antibiotics]”

Mohammed Rafiq

In terms of evidence for topical antibiotics, “there’s not much evidence that [they] are any better than topical non-antibiotics,” Santer says, citing a 2004 study published in The Lancet that showed that topical benzoyl peroxide had similar efficacy to benzoyl peroxide in combination with a topical antibiotic or even an oral antibiotic[4].

“In a lot of cases, topical [non-antibiotic] treatments are just as good,” agrees Mohammed Rafiq, a pharmacist with a special interest in skin conditions, who now does most of his work in primary care.

In his work as a community pharmacist, he gets asked about over-the-counter (OTC) acne treatments once or twice per week. As well as preparations containing benzoyl peroxide, which he advises patients to start at a relatively low dose of between 2.5% and 5%, he also supplies products containing niacinamide, and washes containing salicylic acid.

Mahto says that retinoids (some of which are available OTC), zinc and tea tree oil can also be helpful.

However, if patients need to move on to oral treatments, antibiotics are the first line (see Box). And, consequently, they are prescribed a lot. A study that Santer was involved in estimated that GPs prescribe oral antibiotics at around a third of first consultations for acne[1].

Determining resistance

The key question is how significant the problem of antimicrobial resistance, secondary to long-term antibiotic use, is in acne patients.

The BNF treatment summary for topical preparations for acne states that antibacterial resistance of C. acnes is increasing and that there is cross-resistance between erythromycin and clindamycin; the two topical antibiotics licensed in the UK for treatment of acne vulgaris[5].

“In the UK, resistance is around 65% for erythromycin and clindamycin, and around 20% for tetracyclines”

Heather Whitehouse

It states that, where possible, non-antibiotic antimicrobials, such as benzoyl peroxide or azelaic acid, should be used.

“In the UK, resistance is around 65% for erythromycin and clindamycin, and around 20% for tetracyclines,” explains Whitehouse.

“Globally, this is a concerning upward trend as antimicrobial resistance makes acne harder to treat and there is some evidence for emerging multi-treatment resistant strains.”

Whitehouse highlights a research study she led, which showed that lymecycline was the most commonly prescribed systemic antibiotic (65.1 % of patients) for acne[6].

“At the time of publication, data made available via OpenPrescribing reported an average of 90,302 lymecycline prescriptions per month for the first quarter of 2018 (for all indications, as unable to extract for acne alone).

“Latest comparable data for 2020 shows an average of 88,500 prescriptions, which suggest little change in prescribing patterns.”

What is more, studies have shown that topical antibiotics can cause localised antimicrobial resistance, not only in other commensal bacteria on the skin of the person being treated but also in their close contacts[7].

“Careless administration of antibiotics could therefore result in the spread of resistance to other bacterial species,” warns Whitehouse.

“Beyond acne, erythromycin and clindamycin are commonly used antibiotics to treat things such as upper respiratory tract infections,” she adds.

However, topical antibiotic preparations are thought to make less of a contribution to antimicrobial resistance than oral antibiotics.

“Anything that you take orally is going to have more implications in terms of resistance than if you are just applying something topically to the skin”

Anjali Mahto

“Anything that you take orally is going to have more implications in terms of resistance than if you are just applying something topically to the skin,” says Mahto. This is because there will be more systemic exposure to the antibiotic, which can affect bacterial populations in other parts of the body, such as the gut microbiome.

Bhate is currently conducting a systematic review looking at the potential consequences of long-term oral antibiotics for acne[8]. “If you give long-term antibiotics for acne in a relatively well population, what might happen to them afterwards?” she asks. Bhate and her colleagues are looking to see what the evidence is for later antibiotic failure in this group.

The results of her review are yet to be published and, because the NHS does not have a record of the indications that medicines are used for, it is hard to be sure of the specific burden of prescriptions for acne. However, what is clear is that lower doses and longer durations of antibiotic therapy are associated with an increased risk of antimicrobial resistance by exerting selective pressures, allowing more resistant bacteria to flourish[9].

Bhate says we have no excuse not to act now. “We have evidence to know that antimicrobial resistance is a problem,” she argues. “And we know that we’re giving an antibiotic for acne for longer periods of time.”

Santer agrees. She is one of the authors of a study by researchers at the University of Southampton — which was due to be presented at the Society for Academic Primary Care in 2020 but was cancelled owing to the COVID-19 pandemic — that looked at antibiotic prescriptions in adolescents aged 11 to 18 years, many of which were for the treatment of acne[10].

She and her colleagues found that more than 15% of prescriptions were for long-term antibiotics (28 days or more), and that long-term antibiotic prescribing resulted in a similar magnitude of antibiotic exposure (days of use) as acute antibiotic prescribing in this age group.

“Among young people, long-term antibiotics for acne contribute to a high proportion of the overall volume of antibiotic prescriptions, because so many of them remain on the antibiotics for many months,” Santer says; in the study, the authors call for “urgent action” to find alternative management strategies.

The lack of alternatives

In December 2020, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published its first ever set of draft guidelines for acne[11]. Bhate describes them as being “antibiotic dominant, particularly at the primary care level”, but generally uncontroversial, with little variation from previous guidelines issued by other professional bodies. The issue, she says, is the lack of non-antibiotic oral treatments for acne.

In fact, within a primary care setting, the only alternative is the oral contraceptive pill; but the NICE draft guidelines suggest that clinicians only consider recommending this for people who are already seeking a hormonal contraceptive, in preference to the progesterone-only pill, which is thought to potentially exacerbate acne.

In terms of the antibiotics themselves, the draft guidance warns about antimicrobial resistance, and advises clinicians to always prescribe topical and oral antibiotics in conjunction with a non-antibiotic topical when treating acne, but never together. These strategies are thought to help limit resistance and, although the guideline allows for patients to be on antibiotics for up to six months, it advises regular, 12-weekly reviews.

“You do need to make sure that antibiotics are not just a repeat that’s dished out without actually having clapped eyes on the patient and trying to understand: does this work?” Mahto says.

If it does work, when patients come off oral antibiotics, they sometimes suffer a rebound of their acne. “That’s where maintenance treatment comes in,” Rafiq says. The draft NICE guideline says to consider a fixed combination of topical adapalene and benzoyl peroxide as maintenance treatment for acne. If this is not tolerated, it advises topical monotherapy with a non-antibiotic topical agent.

Even when patients reach secondary care, there is not a huge amount of choice. Isotretinoin can be effective, but it requires regular monitoring and has been associated with sexual and mental health effects, which triggered an ongoing review by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

Other than that, the only other oral treatment in fairly widespread use, at least in the United States, is the, as yet unlicensed, diuretic spironolactone, which seems to work in acne through an effect on androgen receptors.

“That would be a good alternative to oral antibiotics because you can take it slightly longer term,” says Santer, who is one several researchers involved in a large UK trial to determine the effectiveness of spironolactone for acne in women.

Antimicrobial stewardship

Given the lack of alternatives, the key to reducing antibiotic use in acne may lie in making sure that the patients who receive oral antibiotics really need them. “There’s a lot of advice that people need around [non-antibiotic topicals] that they tend not to get at the moment,” says Santer.

Rafiq, who was on the committee that prepared the NICE guidelines but does not speak for them, agrees that pharmacists have an important role in counselling patients on how to use these treatments correctly.

As well as making sure his patients understand what causes acne and how to practise good skin care, Rafiq ensures that they know how to minimise the side effects of a treatment and “that sometimes there’s a delayed effect”.

This, says Santer, is vital. Otherwise patients may decide to “abandon them early” without giving them time to work.

“It does take some time to see the benefits of a new skincare routine,” Mahto adds.

“Your skin cycle [renews] every 28 to 30 days,” she says, and it will take a couple of skin cycles to see the change.

The problem is, Mahto says: “If you’ve got spots and you get given a cream, all you want to do is slap on as much of it as possible.” But this is likely to lead to skin irritation. Instead, she suggests counselling patients to start off slowly and build up their use.

“I think we massively underestimate how much acne will affect people’s self-confidence”

Anjali Mahto

It is no wonder that patients are keen to see the effect of treatment. “I think we massively underestimate how much acne will affect people’s self-confidence,” Mahto says. “Social withdrawal is quite common with acne; anxiety, depression,” she continues.

But if patients present to their GP too soon, before giving topical treatments a proper chance, they may end up on antibiotics unnecessarily.

Santer was involved in a qualitative interview study looking at GP perspectives of acne[12]. The researchers found that, despite the fact that GPs are “increasingly aware of antimicrobial resistance” and the total amount of antibiotic prescribing has fallen by 12% over the past five years, “they appeared to be less concerned about it in the context of acne”.

What is more, Santer says, oral treatments are sometimes perceived to be more effective than they are, by both doctors and patients. “There’s this perception that a pill will sort it”.

And, despite the fact that the evidence is limited, “there’s still this feeling that antibiotics are kind of like a magic bullet.” But, in light of ongoing antimicrobial stewardship efforts, this will have to change.

Box: Treatment choices for acne vulgaris:

- Acne of any severity:

- Fixed combination of topical adapalene with topical benzoyl peroxide

- Fixed combination of topical tretinoin with topical clindamycin

- Mild to moderate acne:

- Fixed combination of topical benzoyl peroxide with topical clindamycin

- Moderate to severe acne

- Fixed combination of topical adapalene with topical benzoyl peroxide plus either oral lymecycline or oral doxycycline

- Topical azelaic acid plus either oral lymecycline or oral doxycycline

- Do not use the following to treat acne:

- Monotherapy with a topical antibiotic;

- Monotherapy with an oral antibiotic;

- A combination of a topical antibiotic and an oral antibiotic.

- First-line treatment should be reviewed at 12 weeks

- Treatment with topical or oral antibiotics should not be continued for longer than 6 months

Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[13]

- 1Francis NA, Entwistle K, Santer M, et al. The management of acne vulgaris in primary care: a cohort study of consulting and prescribing patterns using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Br J Dermatol 2016;:107–15. doi:10.1111/bjd.15081

- 2Stathakis V, Kilkenny M, Marks R. Descriptive epidemiology of acne vulgaris in the community. Australas J Dermatol 1997;:115–23. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.1997.tb01126.x

- 3Zhu T, Zhu W, Wang Q, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility ofPropionibacterium acnesisolated from patients with acne in a public hospital in Southwest China: prospective cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019;:e022938. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022938

- 4Ozolins M, Eady EA, Avery AJ, et al. Comparison of five antimicrobial regimens for treatment of mild to moderate inflammatory facial acne vulgaris in the community: randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2004;:2188–95. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(04)17591-0

- 5Rosacea and Acne. BNF. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/rosacea-and-acne.html (accessed Feb 2021).

- 6Whitehouse H, Solman L, Eady EA, et al. Oral antibiotics in acne: a retrospective single‐centre analysis of current prescribing in primary care and its alignment with the national antibiotic quality premium. Br J Dermatol 2019;:1341–2. doi:10.1111/bjd.18339

- 7Miller YW, Eady EA, Lacey RW, et al. Sequential antibiotic therapy for acne promotes the carriage of resistant staphylococci on the skin of contacts. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 1996;:829–37. doi:10.1093/jac/38.5.829

- 8Bhate K, Lin L-Y, Barbieri J, et al. Is there an association between long-term antibiotics for acne and subsequent infection sequelae and antimicrobial resistance? A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2020;:e033662. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033662

- 9Raymond B. Five rules for resistance management in the antibiotic apocalypse, a road map for integrated microbial management. Evol Appl 2019;:1079–91. doi:10.1111/eva.12808

- 10McKeown S, Stuart B, Francis N. Prescribing of Long-term Antibiotic to Adolescents in Primary Care: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Society for Academic Primary Care. 2020.https://sapc.ac.uk/conference/2020/abstract/prescribing-of-long-term-antibiotic-adolescents-primary-care-retrospective (accessed Feb 2021).

- 11Acne vulgaris: management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-ng10109/documents/draft-guideline (accessed Feb 2021).

- 12Platt D, Muller I, Sufraz A, et al. GPs’ perspectives on acne management in primary care: a qualitative interview study. Br J Gen Pract 2020;:e78–84. doi:10.3399/bjgp20x713873

- 13Acne vulgaris: management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/GID-NG10109/documents/draft-guideline (accessed Feb 2021).